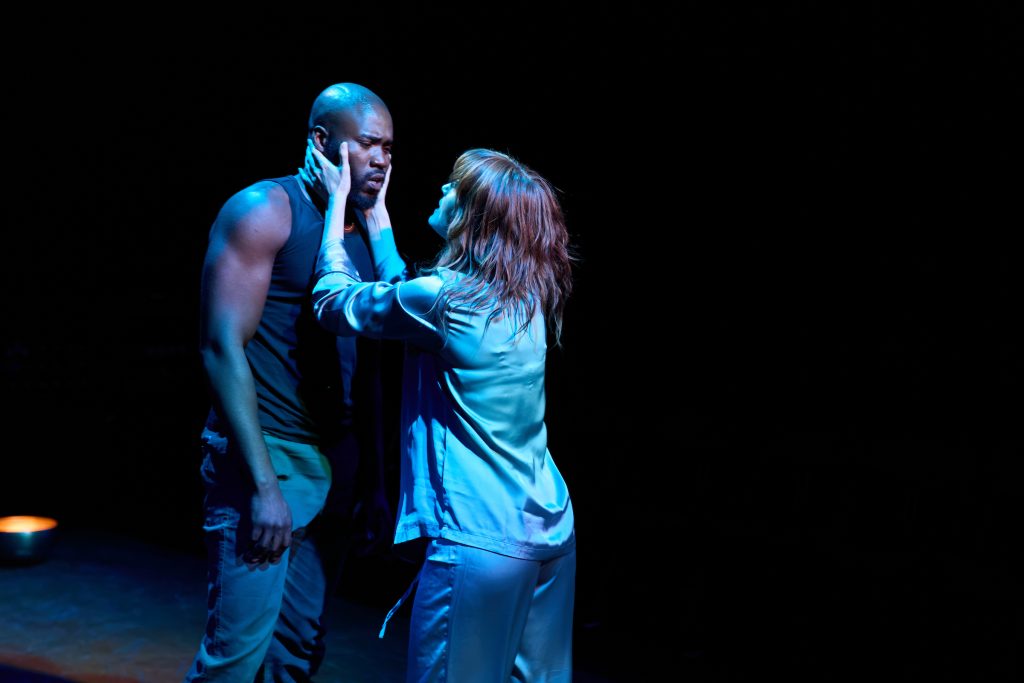

Gillian Greer’s adaptation of Eliza Clark’s novel has a lot to offer – above all a fantastic solo performance from Aimée Kelly. Tension is crammed into the story of a disturbed art photographer, who may be or may not be a serial killer. Not a moment of its 80 minutes is dull. I’m just not sure Boy Parts as challenging as it should be.

Kelly makes our antiheroine Irina hold attention with an acerbic tongue and plenty of extreme views. There’s no doubt about her contempt for people, and her lust for the young men she shoots is uncomfortable to watch. Kelly handles the script’s dark humour with considerable control – and then the next moment gives you goosebumps.

Yet, do Irina’s mental health problems make the play too easy? We are never sure if the dark fantasies are really enacted. Or what role self-medication in the form of drink and alcohol plays. An unreliable narrator can be a great device but, in a one-person show, other perspectives are especially tricky. Maybe the ideas are disturbing enough. But is there the danger we dismiss Irina?

The twist of having a female photographer exploiting men is an interesting one, especially the question about the very possibility of her being a threat. The chills are here, the language visceral. But there’s a snag again. We might wonder how much the work is being shaped by a curator Irina wants to please – and, of course, this gallery owner is a man. And many ideas feel rushed. That Irene dismisses her personal security, her self-esteem, even being abused, all shock – how could they not? – but each needs expanding on.

The production itself is strong. Sara Joyce’s direction is firm, and the show looks great. Peter Butler’s set recalls an exhibition space and benefits the video work from Hayley Egan. The whole show is aided by Christopher Nairne’s cinematic lighting design. But, with all this, we’re moving into the territory of style over substance. Boy Parts is crammed and yet feels fleeting. The show has great moments but doesn’t add up to much.

Until 25 November 2023

Photo by Joe Twigg