Let’s celebrate that Lidless Theatre, which had great success with Philip Ridley’s Leaves of Glass last year, provides the chance to see this 1991 work from the incomparable playwright. The early piece is far from his best work. But Ridley’s writing is so exciting that this story of an encounter between troubled siblings and an odd duo who give the play its title is wild, unforgettable, theatre.

The start is strong. Performed expertly by Ned Costello and Elizabeth Connick, Presley and Haley are twin siblings who are heavily medicated and living as hermits, their lives shaped by routine and fantasy. They repeat and invent stories that defy logic and, like their characters, are full of ambiguity and emotion.

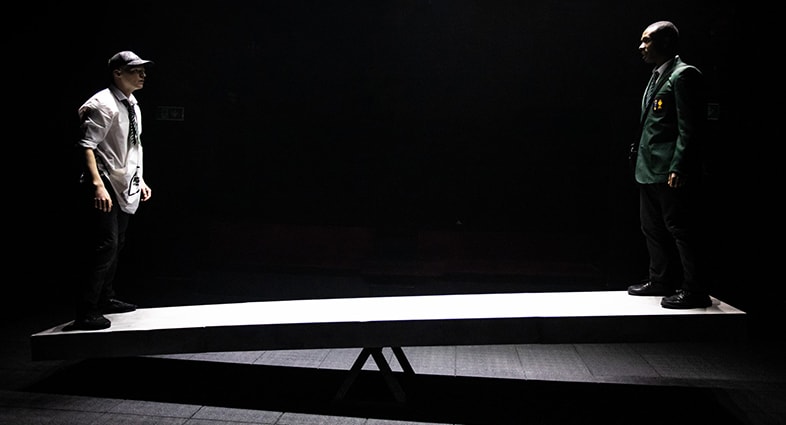

The chance arrival of Cosmo Disney and his sidekick Pitchfork (who is tricky to discuss without spoilers) upsets the scenario less than might be expected – they are an even stranger pair. Pitchfork, played by William Robinson, is a compelling (and dangerous) figure who invokes repulsion rather than magic or charisma. There’s a wonderful variety of abjection, but it is all down to earth.

This is a valid interpretation. Horror is the key and, of course, there is banality in evil. But arguably, director Max Harrison embraces the play’s controversial reputation too forcefully. Discomfort and shock are only part of the play. The stories recounted should – sometimes – offer succour. Disney’s bleak view of human nature might , if not oppose, contrast with the siblings.

A similar position is taken with the tricky comedy in the play. With Ridley, laughs are always barbed – it’s deliberate that not everyone in the audience joins in – but here they are also broad. Too much deadpan delivery is a mistake, and it blunts the script.

Both reservations are subjective. Harrison has his ideas for the play and, if questionable, that vision is consistent, considered and thorough. The performances are committed and the delivery technically accomplished. But I think there’s something missing – a conflict between stories that structure and those that shock. Disney and Pitchfork are showmen and of the moment. The twin’s tales are private and endure. And at least one thing Ridley is asking is which kind of story is more frightening.

Until 4 October 2025

Photos by Charles Flint