Not everyone makes a beeline for Samuel Beckett plays. It sometimes feels as if the legendary modernist is more beloved of theatre-makers than theatregoers. Fans will, of course, jump at the chance to see these seldom performed shorts, but director Richard Beecham’s stylish work and two brilliant performances should also secure appeal for a wide audience.

Footfalls

A woman having bizarre conversation with an offstage voice might sound almost a cliché of experimental theatre. The woman, May, or maybe Amy, may or may not be talking to her dead mother. The voices address one another and then the audience.

The spectre of poor mental health haunts the piece and the appropriately ghostly character, depicted by Charlotte Emmerson, is mesmerising. Emmerson’s timing – so crucial for this piece – is spot on.

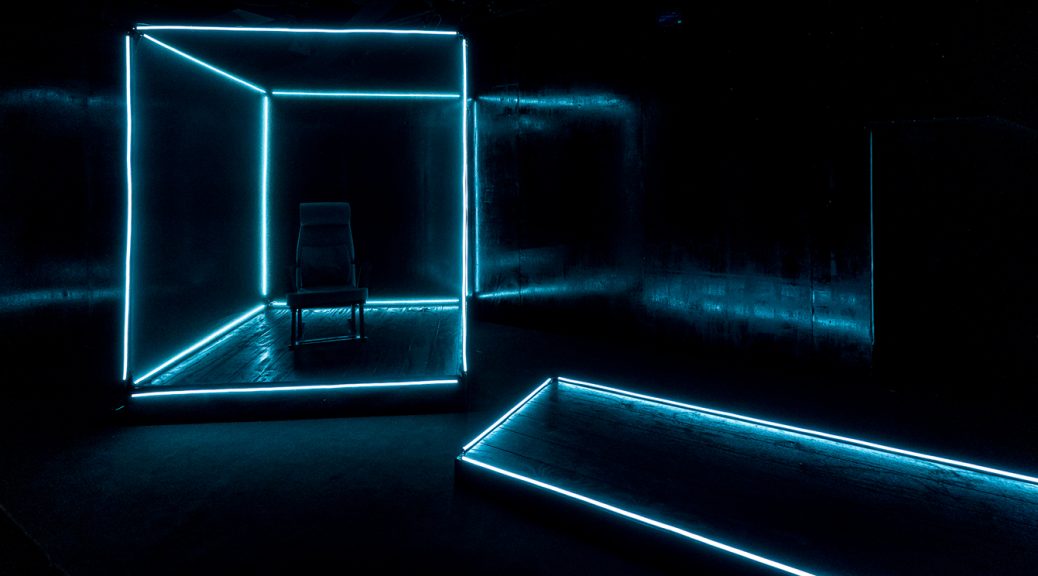

Beckett was specific about staging and instructions for lighting and sound – cleverly elaborated by Beecham and his designers Ben Ormerod and Adrienne Quartly. Within these constrictions, a performance of incredible control notches up the tension marvellously.

Rockaby

The sense of isolation for the lonely old woman in Rockaby is overwhelming. There’s a lot of philosophy again – what kind of existence does this unperceived character have? But sitting in her chair, looking for any sign of life with “famished eyes”, the piece becomes painful and deeply moving.

A brilliant performance from Siân Phillips brings home the emotion within the play. Phillips never finds it hard to be magisterial. And there is a dignity to the character that makes us take her wish for more life seriously. But there’s a frailty, too, which compounds a sense of sadness.

The rocking chair, with credit to set designer Simon Kenny, also becomes a character. And a very spooky one. Is it fanciful to say it has a life of its own? As with the sound design within Footfalls, there’s a quality far from lulling in the ceaseless, yet cleverly varied, presence of its back and forth.

Footfalls and Rockaby are late works, from 1975 and 1980, respectively. Minimal and experimental, they set the mind spinning. Concerning mortality and memory, we are presented with vivid, mysterious characters. That intrigue drives both shows for me. It may be simplistic, and far from grand intentions, but both pieces work as bizarre ghost stories that are strangely exciting as well as profound.

Until 20 November 2021

Photos by Steve Gregson