This live stream of new writing was back for a third evening with a sense of celebration. Its creators have won an award! And they’re starting a fun competition for viewers to name each night – the next one is on 26 August. With congenial host Liam Fleming creating a kind of community before our eyes, this back-to-basics ‘micro theatre’ company is thriving online.

It’s the material that counts, of course, and the four plays presented are of a high standard: writing, direction and performances. There is a bumpy start. Rules by Lucy Jamieson didn’t excite me: the humour behind two flatmates talking about STDs failed, despite Karina Holness and Esme Cooper trying very hard. But it’s a debut piece and Jamieson can learn a lot from the experience.

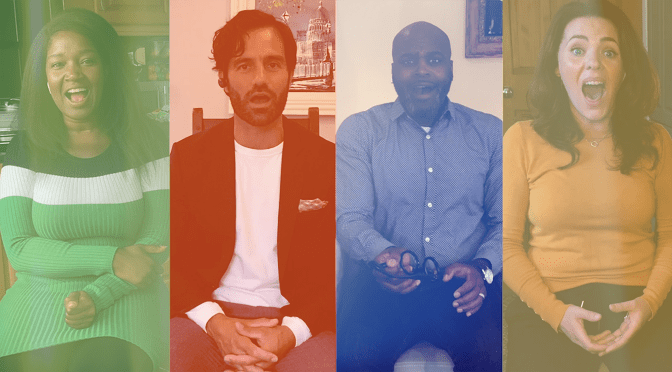

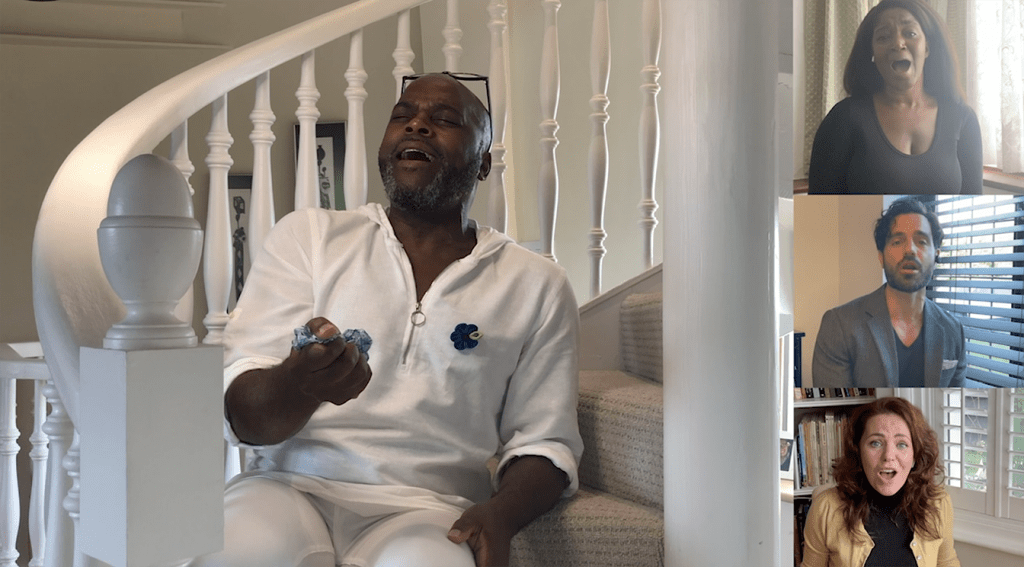

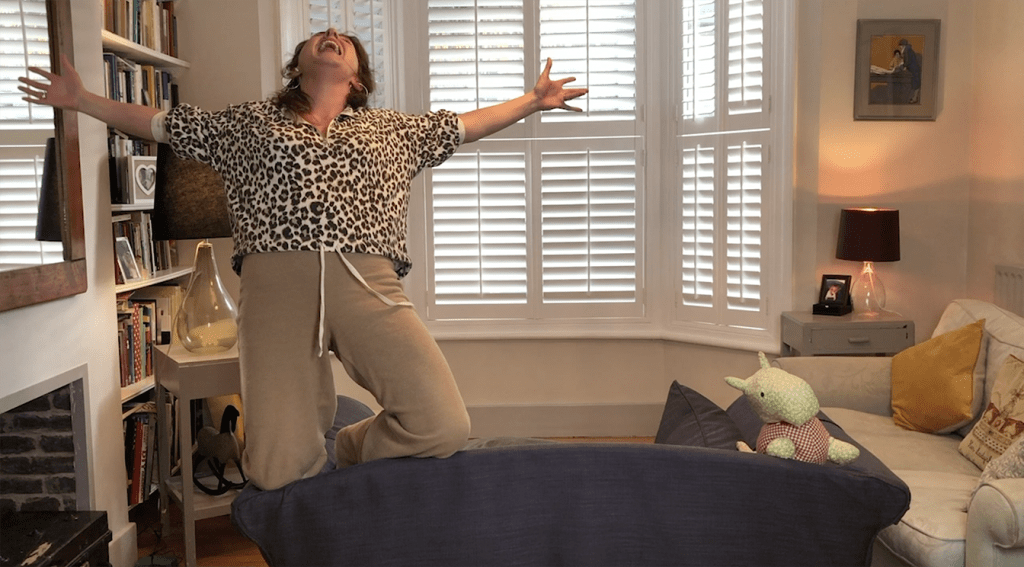

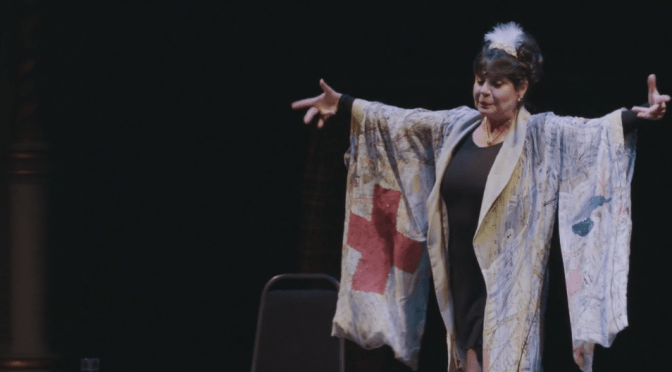

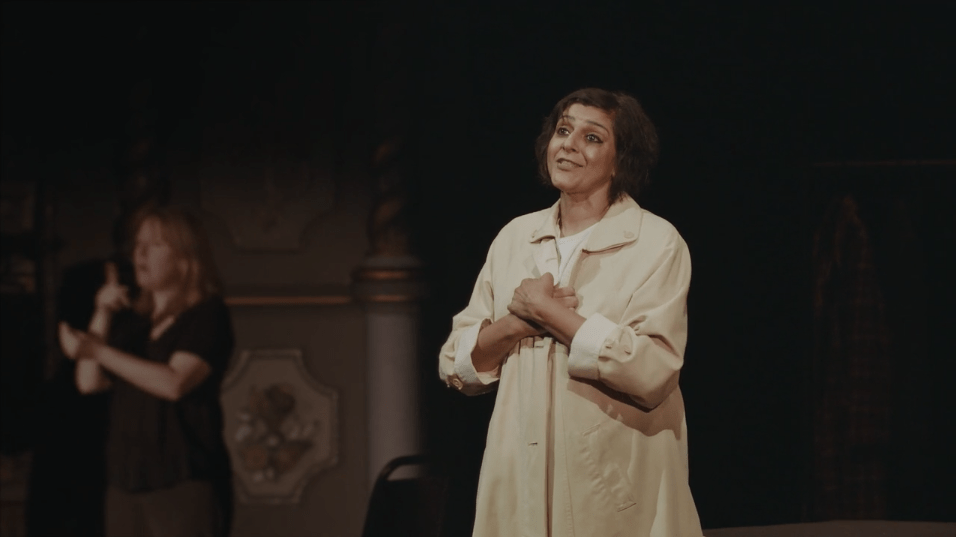

Two monologues showed care, cleverness and depth. Emma Dawson’s Stones Around My Neck makes you question who is gaslighting who in a skilful developing scenario. Kayla Feldman’s confident direction of Deborah Garvey is spot on. Listen by Jacquie Penrose is a cracking piece. Masterfully handling its short duration, adding just enough mystery into a vague apocalyptic setting, this phone message about a relationship that has broken down is great stuff. Aided by Fleming’s direction and (for once) the filming, an emotive performance from Amelia Parillon (pictured top) proves gripping.

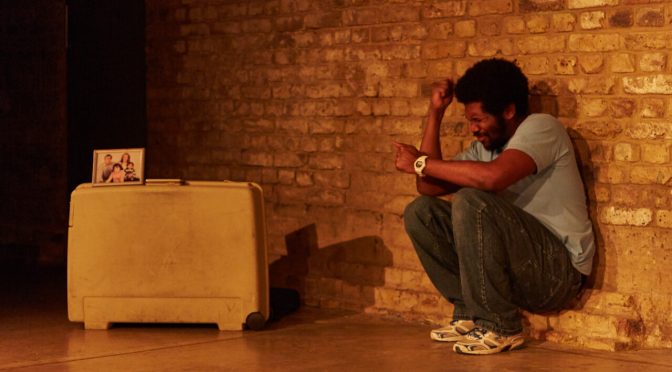

Impressive as the previous piece is, my highlight was James C Ferguson’s The Chair – a deliciously wicked comedy sketch with teeth. Where the bite actually comes from is the source of surreal humour as we learn “the particulars” of two dinner guests’ disappearance. Ferguson’s language has a distinctive quality. And performers Andrew Gruen and Amy Fleming, under Jonathan Woodhouse’s direction, control their overblown characters very well indeed.

My only problem came at the end of Bare Essentials 3: with a Vengeance. Although bringing all the performers back for a bow was deserved, I still feel uncomfortable clapping a computer screen. Wouldn’t it be great to get back to real-life curtain calls? With Encompass Productions usually based in bars, maybe someone could lend a pub garden? Given what has already been achieved, if anyone can manage this next step it’s this team. Fingers crossed.